Here We Go Again Pants Zipper Meme

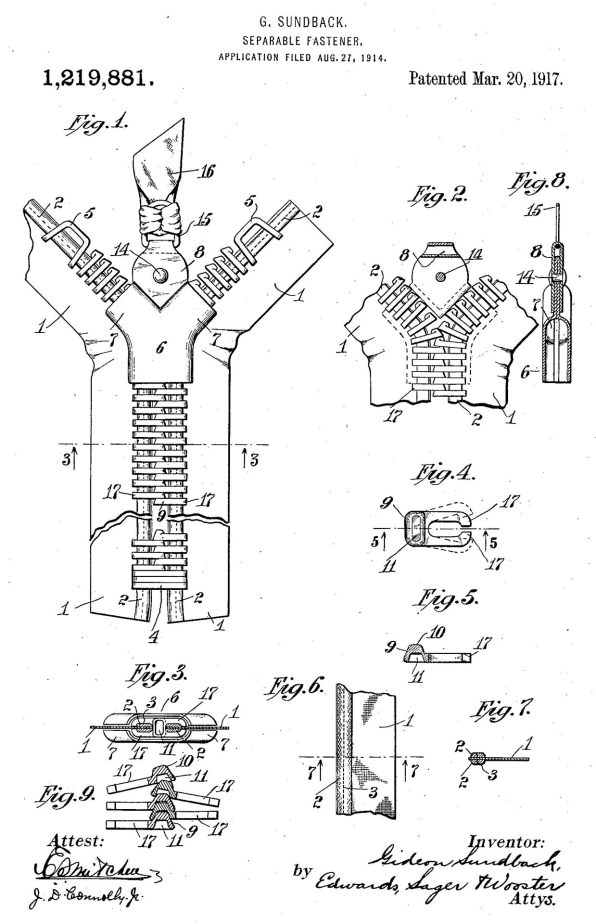

Combine two rows of fine teeth that lock together, a slider and a tab, and all of a sudden you accept a quick way of securely closing a bag, jacket or pair of pants–a zipper. These handy, everyday devices were invented in the United States more than a century ago merely are now global. They are manufactured in many places, sewn or glued in place pretty much everywhere and used absolutely everywhere. Merely however apprehensive and ubiquitous the attachment may seem, information technology currently carries a Japanese passport with a lot of Chinese visas. To larn more, allow's goose egg through a historical overview, a few pieces of international-trade theory and a look at the ongoing market place battle.

YKK, advantage Nippon

Take a sample of five items in your dress closet and examine the tabs on any zippers. Odds are that at least one is marked with the lettersYKK. It was made past a Japanese firm, currently the earth's top zipper manufacturer, with $10 billion in annual revenue and a 40% global market place share–pretty impressive.

And then how did 1 Japanese company achieve this happy position? Does it have something to practice the comparative advantages of Japan which, as British economist David Ricardo explained in 1817, requite rise to trade between nations? Not actually. The land of the ascension lord's day never specialized in zippers or more than broadly in light manufacturing. Above all the success of YKK zippers is not due to exports. Instead, it's well-nigh a unmarried business firm investing abroad to set up factories. It is now represented in 73 dissimilar countries through about 100 wholly endemic subsidiaries.

A U.S. invention in the dwelling of blue jeans

If anywhere ever enjoyed a comparative advantage with respect to zippers information technology was the Us. That'due south where the device was invented and, afterward some difficulty, finally adopted. The saga of the U.Due south. zipper is told in a thorough but entertaining book by Robert D. Friedel, professor of history of applied science and scientific discipline at the University of Maryland. He sees the zipper every bit the emblematic invention no 1 needs but which ultimately prevails, admitting laboriously. Twenty-five years passed between 1893, when the original patent was filed, and its first actual use on rubber galoshes. Here indeed was an innovation desperately seeking an application. For many years tailors and garment manufacturers made do with hooks, buttons, and ribbons. They were cheap and like shooting fish in a barrel to replace, with a broad range of colors and uses. But the demand for speed and fashion's appetite for novelty finally prevailed to make the zipper an essential accessory.

Blue jeans are a perfect case of this procedure. Levi'south brought out its first model with a zipper in 1947. The San Francisco–based firm was looking for a way to interest East Coast women, suspected of having doubts almost the rather visible button fly. So zippers (as they're called in the U.s.a.; in the U.M. they're known every bit zips) entered the fray as an alternative to wing buttons. We know now which one came out on top–just think of the sleeve of the Rolling Stones' LPViscous Fingers.

Talon tumbles

But peradventure we should get dorsum to the The states and international trade. In the 1960s the incumbent zipper manufacturer, Talon, enjoyed a comfortably dominant position in its abode market. Its name featured on seven out of x tabs. But a decade later it had lost half its market share and these days it barely rates but a few percentage points. This was a classic instance of a monopoly coming unstuck after resting also long on its laurels. It didn't exercise enough to improve productivity, and so its prices were as well high; it failed to innovate, consequently neglecting new applications such as handbags, luggage or outdoor gear; averse to risk, information technology exported little, despite the fact that cloth manufacturing was fast relocating.

In short, it took the exactly contrary course from YKK. Shortly after the Japanese firm was incorporated, it started building its ain machines to reach faster, higher-quality product. It likewise went away, soon setting upwards subsidiaries in Malaysia, Thailand, and Costa Rica. It start appeared in the U.South. market in 1960, marketing zippers that were cheaper than Talon's and comparable, if not meliorate. YKK'south first US production unit followed 12 years later on. In a humiliating blow to Talon, the pressure suits worn by the first ii astronauts to walk on the moon were fitted with YKK zippers.

Home market, exports, direct investment

There are several lessons in international trade to be learned hither.

First, comparative advantage, once sought betwixt rival nations, now operates between firms. Why do some only serve their home market, whereas others consign and others still open subsidiaries abroad?

In the mid-1970s Professor John Dunning, of Reading University, provided an initial insight at a symposium in Stockholm. Drawing together several strands of economical theory he proposed an eclectic matrix for analyzing foreign direct investment past multinational corporations such as YKK. He focused on several factors, including the advantage of belongings various specific assets. For our champion zipper manufacturer, one of these assets was its machine-tool know-how. Different its competitors, the Japanese firm based its expansion on developing its own materials and equipment. From the starting time it designed its own tools and fed them proprietary materials. It but purchased plastic pellets and a mixture of alloys of its ain invention. YKK operates along like lines to Michelin, the France-based tire manufacturer, closely guarding the cloak-and-dagger of its manufacturing processes and making constant improvements. This is a situation completely at odds with 1 in which the aforementioned suppliers serve the same customers. In the latter case, the customers share the same intermediate consumption and machines, leaving no scope for differentiation with regard to these factors and hence no scope for comparative advantage.

A second insight, which we owe to Professor Marc J. Melitz of Harvard Academy, has the advantage of existing equally a formal model. He developed an entry-exit model for firms operating in the same manufacture but with varying degrees of productivity. On the basis of this difference they fall into one of iii categories: the near efficient serve the home market and export; the slightly less efficient ones only cater for the abode market place; the least efficient fold. Simply the ranking is dynamic, shifting according to hindrances to international merchandise, notably ship and information costs, and import tariffs. When the effect of such obstacles declines, pushed downward by technical progress or the opening of borders, new firms will export, whereas a further cohort of poor performers volition get to the wall, their sales on the dwelling market captured by the remaining, more efficient firms.

Melitz breaks new ground in demonstrating new gains from liberalizing trade: reallocation, in the same industry, of production by the least efficient firms to their virtually efficient competitors. In other words, globalization, which enlarges the potential market, has the effect hither of increasing average productivity in a given industrial sector. For example, the market share lost by Talon and taken up by YKK uses less labor and less uppercase to manufacture one meter of zipper.

Under equivalent competitive atmospheric condition this will do good the consumer because the price volition exist lower. Which is indeed the case in Melitz's model. The same competitive authorities prevails regardless of how open up international trade may be. At equilibrium all the firms cover their average unit of measurement cost and none of them behave strategically. The firms become on operating as separate entities, as in a situation of perfect contest.

Yet international merchandise by and large encourages the emergence and consolidation of powerful firms with substantial market share, or in other words, oligopolies which coalesce and gather force. Then information technology changes the intensity and competition regime.

Toward a global duopoly

The attachment concern has gradually evolved from one dominated by national champions, each initially entrenched on their domicile ground then challenged by imports from the most enterprising of their foreign rivals, to a market place in which a dominant multinational, YKK, coexists with a competitive fringe comprising several hundred, mainly Chinese companies. In recent years the competitive situation has shifted over again, through consolidation of the zipper industry in the People's Democracy of Red china. In that location are now a dozen or so firms, all with iii-letter names. Some, such as YCC or YQQ, make no secret about trying to closely mimic their large Japanese rival.

Ane of their number, SBS, is listed on the Shenzen stock commutation and stands out for its size and ambition. It leads the pack in terms of the number of patents it has filed, overall output and the share it exports (about 25%). It makes no bones about being out to beat YKK.

And so a global duopoly is taking shape. Just this has in no way reduced the intensity of competition. The 2 companies eagerly dispute each other's position in various market segments. SBS is shifting up-market with better-quality metal or fifty-fifty plastic zippers. Information technology already supplies customers such equally Adidas or the French sports retailer Decathlon, which will not accept zippers that jam after only 1,000 cycles.

Simply it volition take SBS a long fourth dimension to outdo YKK'southward comparative advantages. Operating close to its customers thanks to subsidiaries all over the globe, the Japanese firm also wields considerable technological ascendancy, due to its R&D centers, machine and engineering grouping, and production plants. At the aforementioned time YKK, which holds a 40% share of the global marketplace by value but merely 20% by volume, has decided to move out of its comfort zone–in the middle and upper echelons of the market–and dispute its rival's supremacy over the budget end of the market.

No ane knows how this contest will pan out. The most likely outcome would be a duopoly, if only because the big firms using big volumes of zippers exercise not want to have to come to terms with a single supplier.

But at a time of open merchandise warfare and exacerbated economical nationalism, it would exist a mistake to rule anything out: Not even a tweet announcing dissuasive tariffs on the import of Chinese zippers to the Usa on some highly strategic pretext, nor yet the expulsion of YKK from Chinese markets on the grounds of domestic security, industrial espionage or infringing SBS patents. Peculiarly if the zipper 1 day becomes a connected object capable of gathering data on a wearer's movements. Of course, one mode of avoiding a zipper war would be go dorsum to good, old buttons.

François Lévêque is a professor of economics at Mines ParisTech, and the writer of "Competition's New Apparel: twenty Short Cases on Rivalry betwixt Firms." This essay outset appeared at The Conversation.

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90321912/the-global-zipper-war-is-heating-up

0 Response to "Here We Go Again Pants Zipper Meme"

Post a Comment